Yas, Queen

Egyptologist Kara Cooney stops in Spokane to talk about Egypt’s female kings, and why women in power still scare us

The first installment of Best of Broadway Spokane’s 2020 National Geographic Live! series features Egyptologist Kara Cooney, presenting “When Women Ruled the World.” Cooney is a UCLA professor and earned her Ph.D. in Egyptology from Johns Hopkins University. She hosted Discovery Channel’s 2009 series Out of Egypt, and has published two books on women leaders in ancient Egypt, including 2018’s When Women Ruled the World: Six Queens of Egypt. Besides the complex gender politics of the 5,000-year-old civilization’s reign, Cooney also studies ancient Egypt’s economics and authoritarian government. We chatted ahead of her talk Feb. 13; responses have been lightly edited for length and clarity.

INLANDER: How do you piece together fragments of historical evidence to create a cohesive narrative about ancient Egypt’s female rulers?

COONEY: You’re hitting on Egyptology’s biggest problem. Egyptology is studying an authoritarian regime, and in those regimes they don’t reveal in written form the foibles or competitions between leaders. It’s a hard thing when you’re talking about a regime that perfects and divinizes their rulers. There is also no real politics in the historical record, there is just the perfect “god wanted it to be this way” kind of story. So it’s up to Egyptologists to pull the veils aside and try to imagine the real politics going on behind the scenes.

To fill in those blanks, I use my historical and anthropological understandings of power and how human beings, particularly elite humans in competition with one another, try to gain power vis-a-vis the king or female king.

What do physical artifacts and records tell us about Egypt’s female kings?

Most of the information … is what’s provided by the kings themselves. So for dynasty one’s Merneith, I have her tomb with 120 sacrificial victims, and the tomb of her husband and her son with many more. You can tell a story out of that archaeology.

For Neferusobek of dynasty 12, I’ve got a statue and a couple fragments of inscriptions, and her mention in king lists. Otherwise, there is almost nothing, except to say, “My god, this is the first female king, how are we to understand this?” For somebody like Hatshepsut of dynasty 18, you have all of the buildings that she produced and then all of the erasures her nephew performed after her death. So you have another compelling story to tell: She creates all of this stuff and then her images are erased or smashed.

In each case, the things that are left behind can indeed tell a story, whether they be a grave or a temple or a statue.

What are some of the biggest historical myths about women in Egypt?

I’ve noticed that in textbooks about ancient Egypt these women are used as a kind of revisionist history to give girls — and boys — an idea that women can indeed rule. There is nothing wrong with that, but it can go too far with the false idea that Egypt allowed women to rule, and that they somehow changed the system. I’m not here to write revisionist history, I’m here to find patterns and understand why human beings are hostile to female rule and how Egypt was able to transcend that. But Egypt is a patriarchal system just like anywhere else. These women are there to support the most authoritarian and the most patriarchal of divine kingship and that’s the reason they are allowed in.

What are you working on now?

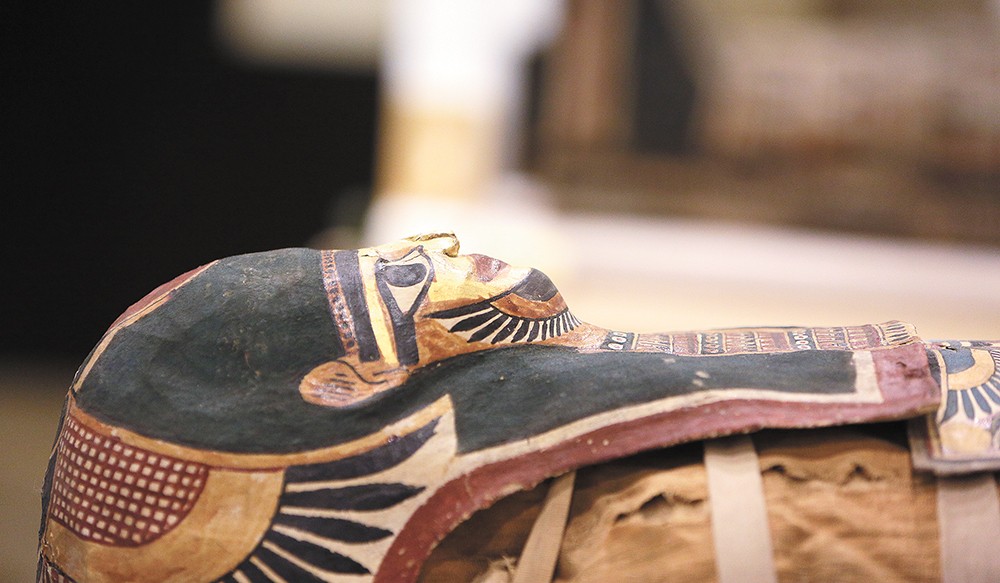

My current research is on the reuse of 21st dynasty coffins. In the Bronze Age collapse, people couldn’t get wood for coffins. But instead of getting rid of this expensive, material burial, the elites decided to reuse coffins of their ancestors: Take one mummy out and take the coffin back to the workshop and have it replastered and painted, and put the freshly dead mummy inside. I’ve looked at over 300 coffins around the world on display and in storage and found about a 70 percent rate of reuse with just my two eyes and a flashlight. It’s kinda crazy.

What was it like to work at Egypt’s archaeological sites?

In my early fieldwork I was excavating in tombs, and when you’re working in tombs you’re dealing with spaces that have been pawed through by so many people, usually treasure hunters. So you’re working in a space filled with bits of bodies: a head here, a torso here, a hand there; coffin bits, bandages, little bits of tchotchkes, canopic jar fragments; everything you can imagine to bury the dead are there.

I found a human hand that still had all the markings of skin, fingerprints and lines. It had cuticles and nails. As I was holding that hand, I could see my mother’s hand in my mind’s eye. It kind of freaked me out, that moment of realizing the humanity of these people I’ve been studying. It’s so easy for historians to separate ourselves from these people, to make them fantastic. But when I was holding that hand, I realized that they’re the same as me. And that is how I go about my work. I try, whether it’s a king or commoner, to think what a human reaction would be to a given situation and try not to make them different or fantastic, or separate them from our own modern reality. Yeah, we have technology and cars, but that doesn’t mean we don’t care about the same things, and have the same anxieties and hopes and dreams. ♦